Message from the Comptroller

A robust labor force is critically important for employers to succeed and grow in New York, and it matters for the fiscal health of the State and local governments. New York’s strength has long been that its workforce is more diverse, unionized, and highly educated than the rest of the nation.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the State’s labor force was more severe than in other states: the size of the workforce declined more rapidly than the rest of the nation in 2020 and continued to shrink in 2021 when other states recovered. In 2021, the State’s unemployment rate was third highest in the country and New York had a greater share of underemployed workers than the rest of the nation. One reason is New York has not recovered from its steep pandemic-era job losses. Although these job losses were not as pronounced in high-skilled industries, recovery has lagged in many industries with high shares of low-wage workers.

New York’s workforce was 1 percent smaller in 2021 than it was in 2011; in contrast, the workforce in the rest of the nation increased by 5.1 percent in this period. New York’s workforce decline is due, in part, to population changes as well as a smaller share participating in the labor force. The only group that has realized significant population and labor force growth over the past decade is the group over the age of 65, suggesting that many may have put off retirement or decided to return to the workforce. While the workforce has begun growing again in 2022, it is still down by over 400,000 people from its peak in December 2019.

Collectively, these trends suggest that challenges may lie ahead with implications for employment levels, economic growth, State and local tax collections, and services supported by those taxes. The Office of the State Comptroller will continue to monitor labor force data, and to provide insights into the composition and changes that occur, in order to help leaders take actions and make decisions that will support the growth and development of this critical element of the State economy.

Thomas P. DiNapoli

State Comptroller

Executive Summary

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides data on both aspects of the labor market — the demand side, or the businesses that provide jobs, and the supply side, or the people who work those jobs. Businesses report full-time, part-time and seasonal employment figures based on persons on the payroll and the location of business operations. On the other hand, labor force figures are reported by households and count the number of workers, whether they are either employed or unemployed. Workers who work more than one job are only counted once and are identified by their place of residence and not by place of work. Employed workers include agricultural workers, as well as the self-employed.1

Figure 1 compares the labor force and employment in New York over the past 10 years. As shown, the number of jobs closely follows the same trend as the number of employed workers, with both increasing from 2011 to reach new highs in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic spurred a sharp contraction.

FIGURE 1: Total Employment and Labor Force, New York, 2011-2021

Notes: Amounts in thousands. Chart starts at a non-zero baseline.

Sources: New York State Department of Labor; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

This report examines trends in the labor force, for both the employed and unemployed, prior to, during and in the year after the pandemic. It also analyzes changes in the population for certain demographics and the proportion of those populations who are in or out of the labor force. Major findings include:

- Between 2011 and 2021, the size of the New York labor force declined 1 percent while it grew by 5.1 percent in the rest of the nation. The labor force declined at a much greater rate than other states in 2020, and while the rest of the nation recovered some of its workforce in 2021, New York’s labor force continued to shrink.

- Only three of the 10 regional labor market regions of New York were larger in 2021 than they were in 2011: Long Island, New York City, and the Hudson Valley. Even prior to the pandemic, over half of the regions were losing workers. Regions with the largest labor force decreases also experienced the greatest population declines.

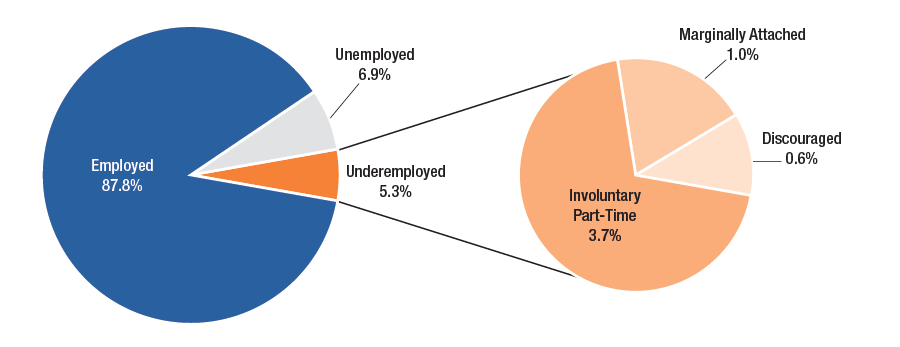

- The State’s unemployment rate (6.9 percent) was third highest in the nation in 2021, due mostly to the high unemployment rate in New York City. In addition to these workers, underemployed workers, who are discouraged, marginally attached to the labor force, or underutilized (involuntary part-time), comprised a larger share (5.3 percent) of the New York workforce in 2021 than in the rest of the nation (4.2 percent). Of the underemployed, almost three-quarters were involuntary part-time workers.

- New York’s labor force participation rate is among the lowest in the nation (ranked 40th), averaging over two percentage points less than the rest of the country in the last 10 years.

- There are more women as a share of the workforce in New York (47.6 percent) than the rest of the nation (46.9 percent); however, women’s participation rate is lower in New York (54.1 percent) than in the rest of the nation (56.2 percent). In 2020, more men left the workforce than women.

- New York’s workforce is more diverse than the rest of the nation. Labor force participation in New York is lowest for Black or African Americans and decreased steadily from 2014 to a low of 55 percent in 2020, rebounding in 2021 but still well below 2011 levels. In contrast, participation rates were highest for Hispanics or Latinos (just over 61 percent on average over the 10-year period), who were the only group for whom participation rates did not decline during the pandemic.

- New York’s workforce is more highly educated than the nation’s, with 50.6 percent of those aged 25 and over holding a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 43.3 percent nationwide. The labor force for this group grew by over 100,000 workers in 2020 alone, and increased 26.3 percent between 2011 and 2021. In contrast, both the population and labor force declined across all other education levels.

Labor Force

BLS defines the labor force as the portion of the population aged 16 and older that is either employed or officially considered unemployed, not including those who are inmates, residents of institutions or on active duty in the Armed Forces. Those who are officially considered unemployed do not have a job, but have actively looked for work in the previous four-week period.

In 2021, there were over 9.4 million people in the labor force in New York, 5.8 percent of the national labor force, ranking it fourth in the nation behind California, Texas and Florida.2 However, while these other states realized labor force growth over the past 10 years, New York lost over 96,000 workers. As shown in Figure 2, New York’s labor force was 1 percent lower in 2021 than in 2011; in contrast, the workforce grew 5.1 percent in the rest of the nation.

FIGURE 2: Cumulative Labor Force Growth, New York and Rest of United States, Indexed to 2011

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

With the Great Recession having a lesser impact in New York than in other states, its labor force grew at a faster pace from 2007 to 2009. However, due to the slow recovery in the years following, New York’s employment growth lagged that of the nation as a whole; New York’s unemployment rate increased, resulting in workers dropping out of the labor force.

As the economic expansion took hold and the employment picture brightened, the labor force in New York rebounded, finally exceeding its pre-recession levels in 2017. This growth persisted until 2020. According to the Index of Coincident Economic Indicators published by the New York State Department of Labor, the New York economy entered a recession in November 2019. This, along with the early impact from the COVID-19 pandemic, caused the labor force to decline at a much greater rate than other states in 2020. The following year, the rest of the nation recovered some, but not all, of its workforce, while New York’s continued to decline.

Within the 10 labor market regions of New York, only three have grown in the past 10 years, as shown in Figure 3. Even prior to the pandemic, over half of the regions were losing workers. Both the North Country and the Southern Tier experienced double-digit declines over the decade; the Southern Tier lost 39,800 workers, 12.6 percent of its labor force, and the North Country lost 10.3 percent.

FIGURE 3: Cumulative Labor Force Growth, Labor Market Regions in New York, Indexed to 2011

Source: New York State Department of Labor

A factor influencing the labor force in the different regions of the State is population change, especially that of the working age population. As shown in Figure 4, the regions with the largest labor force decreases were those with the greatest population declines. Population grew in the regions that expanded their labor forces.

FIGURE 4: Change in Labor Force and Population Aged 16 and Over by Labor Market Region, 2011-2021

Note: Population includes institutionalized persons and military personnel.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau; New York State Department of Labor; OSC calculations

Unemployment

Prior to the pandemic, New York’s unemployment rate was tracking slightly higher than the rest of the nation. (See Figure 5.) With the State being one of the first states impacted by COVID-19 as well as having a pandemic recession longer than the national one (7 months in duration versus 2 months), the unemployment rate was nearly two percentage points higher than the rest of the nation in 2020.3 Compared to the other states and the District of Columbia, New York had the fifth highest unemployment rate (9.9 percent). Nevada ranked first with a rate of 13.5 percent while Nebraska had the lowest, (4.1 percent).

In 2021, the State’s unemployment rate dropped to 6.9 percent, three points lower than the previous year, but over one and one-half points higher than the rest of the nation. New York still had one of the highest unemployment rates, ranking third behind California and Nevada.

Federal pandemic relief programs enacted in 2020 and 2021 provided additional unemployment benefits to those typically eligible as well as providing benefits to those previously ineligible (such as the self-employed).4 While the expanded eligibility resulted in a large increase in the number of people filing unemployment claims, it had little impact on the unemployment rate as most of these beneficiaries were already counted as part of the labor force.

FIGURE 5: Unemployment Rates, New York and Rest of United States, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Except for the Capital Region, the downstate regions had lower unemployment rates than their upstate counterparts and even the rest of the nation prior to the pandemic. In 2020, this changed as the upstate regions tended to fare better; New York City’s unemployment rate spiked to 12.4 percent and continued to be high in 2021 at 9.9 percent.

FIGURE 6: Unemployment Rates by Labor Market Region, 2019-2021

Source: New York State Department of Labor

As pandemic restrictions eased in 2021, unemployment rates throughout the State declined. The majority of regions had rates below that of the rest of the nation; half were within one percentage point of their pre-pandemic rates. In the North Country, the 2021 rate was lower than its 2019 level and the lowest in at least 30 years.

Unemployment is a coincident (“same-time”) indicator of how the economy is doing. When unemployment increases, it typically relates to an economic slowdown as businesses shed workers because their activity has declined. The duration of unemployment is a lagging indicator; that is, it points to how well or poorly the economy was doing in a prior period.

As shown in Figure 7, unemployment in New York increased during the Great Recession, but, of those unemployed, over 60 percent were unemployed 14 weeks or less in 2007 and 2008. However, employment recovery in the years following the Great Recession was slow, taking almost five years for employment to return to pre-recession levels. As a result, the duration of unemployment stayed at elevated levels, with the largest number of people being unemployed 52 weeks or more from 2010 to 2013.

FIGURE 7: Number of Unemployed in New York by Duration of Unemployment, 2007-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

In 2020, as unemployment spiked, nearly three out of five workers in New York who lost their jobs were unemployed 14 weeks or less. The median duration of unemployment at this time, 12.2 weeks, was just slightly higher than in the first year of the Great Recession.

Although the number of unemployed declined in 2021, the length of unemployment increased. In New York, over half of these workers were unemployed 27 weeks or more. The federal pandemic relief programs extended the period by which unemployment benefits could be claimed in addition to increasing the amount, possibly resulting in longer periods of unemployment. With a median of 28.9 weeks, the duration of unemployment in New York was the second highest among the states; Nevada was first with 30.1 weeks.

Another reason for longer periods of unemployment may be that New York has not yet recovered all the jobs lost during the pandemic. New York lost almost 2 million jobs in early 2020, with almost two-thirds of job losses in public-facing industries, such as leisure and hospitality, retail and wholesale trade, healthcare and social assistance, and other services (like personal care salons). The recovery has varied widely by industry, but recovery rates at the end of 2021 were among the lowest in these industries.

Underemployment

As noted previously, the official unemployment rate only encompasses those persons who do not have a job and have looked for work in the past four weeks. A broader measure, the underemployment, or underutilization, rate includes those people who are marginally attached to the labor force, those who are unemployed, available and want a job, but have not looked for a job in the past 12 months. It also includes discouraged workers who are not currently looking for work because they think there are no jobs available, as well as those who are working part-time but would rather work full-time.5

With the pandemic recession, the unemployment rate in 2020, 9.9 percent, exceeded the rates realized during the Great Recession. Underemployment also increased, adding an additional six percentage points, resulting in a total underemployment rate of 16 percent. In 2021, it dropped to 12.2 percent, over five percentage points higher than the unemployment rate of 6.9 percent.

FIGURE 8: Composition of the New York Workforce, 2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

As shown in Figure 8, the underemployed comprised 5.3 percent of the total workforce in New York in 2021, which was higher than the 4.2 percent share in the rest of the nation. Of the underemployed, almost three-quarters were involuntary part-time workers.

Involuntary part-time workers are those who have part-time jobs but would rather work full-time, also known as those working part-time for economic reasons. These include people who are unable to find full-time jobs or those whose hours have been cut back. During and after the Great Recession, the share of the labor force that was employed involuntary part-time increased significantly both in New York and the rest of the nation. This share stayed elevated throughout the first half of expansion, and then declined from 2014 to 2019.

Through 2018, New York typically had a smaller share of its workforce working part-time involuntarily compared to the rest of the nation. (See Figure 9.) However, that changed in 2019 and the gap between New York and the nation became more pronounced on this metric during the pandemic and into 2021. In 2019, 2.8 percent of New York workers were involuntary part-time workers compared to 2.7 percent in the rest of the nation; by 2021, the rate was 3.8 percent in New York and 3.0 percent in the rest of the nation.

FIGURE 9: Involuntary Part-Time Workers as a Share of the Labor Force, New York and Rest of United States, 2008-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Labor Force Participation

While statistics on the labor force show the number of people working or actively looking for work, they do not cover the total population of people aged 16 and over who could work (the working age population). The labor force participation rate represents those who are actively part of the labor force as a proportion of the working age population.

There are a variety of reasons why a person may not participate in the labor force. For example, people between the ages of 16 and 24 are more likely to be in high school or college, while those over the age of 65 are more likely to be retired. Others who are out of the labor force could include those with disabilities, stay-at-home parents, or caregivers for family members. While participation in the labor force may be fluid for many workers, consistently low or falling participation rates may impede potential economic growth; for example, businesses may not be able to find workers to fill critical positions.

New York has historically had lower labor force participation than other states. Its labor force participation rate has averaged over two percentage points less than the rest of the nation in the last 10 years, ranking it 40th among all the states. As shown in Figure 10, New York’s neighboring states, as well as most of those with similar populations, have higher participation rates. Florida is the only exception with a possible reason being that the state has a higher share of its population being of retirement age (aged 65 and over).

FIGURE 10: Ten-Year Average Labor Force Participation Rates, Select States, 2011-2021

| State | Average Participation Rate |

National Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Vermont | 66.9% | 12 |

| Connecticut | 65.9% | 15 |

| Massachusetts | 65.7% | 16 |

| Texas | 64.2% | 20 |

| New Jersey | 64.1% | 21 |

| Pennsylvania | 62.7% | 30 |

| California | 62.3% | 32 |

| New York | 60.7% | 40 |

| Florida | 59.4% | 42 |

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

Labor force participation rates in all states stayed relatively the same in the years prior to 2020. However, the pandemic caused a decrease in participation in 2020; New York’s being steeper than the rest of the nation (1.7 percentage points and 1.3 percentage points, respectively). This decline continued, albeit slightly the following year.

In 2021, the labor force participation rate in New York was 59.0 percent, almost three percentage points lower than the rest of the nation and nearly two percentage points below its pre-pandemic level. The State ranked 41st among the states; Nebraska had the highest participation (69.5 percent) while West Virginia had the lowest (54.7 percent). Only Oregon and Alaska had participation rates exceeding theirs in 2019. The impact of federal unemployment relief programs on participation rates is unclear.6

Within the State, New York City’s labor force participation rate has historically trailed that of the rest of the State. However, as shown in Figure 11, the participation rate outside New York City declined in 2014 before staying essentially the same over the next five years. New York City’s rate had been relatively flat, averaging 60.3 percent annually from 2011 to 2019.

FIGURE 11: Labor Force Participation Rates, New York City and Balance of State, 2011-2021

Source: New York State Department of Labor

While the gap between the participation rates in and outside of New York City narrowed prior to the pandemic, it widened again in 2020, as New York City’s rate dropped to 58.1 percent. In 2021, workers in the rest of the State continued to leave the workforce, but in New York City, they returned; as a result, the gap was largely closed.

Labor Force Demographics

Gender

The proportion of the labor force in New York comprised by men and women has not changed significantly in the last 10 years. In fact, the shares were the same in 2021 as they were in 2011, 52.4 percent and 47.6 percent for men and women, respectively. As Figure 12 shows, women comprise a larger share of the labor force in New York than in the rest of the nation.

FIGURE 12: Share of Labor Force by Gender, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Despite being a smaller share of the total labor force, women in the labor force are more likely to be employed than their male counterparts. In the early years of the last economic expansion, the unemployment rate for women was, on average, over one percentage point lower than that for men. (See Figure 13.) Women continued to have slightly lower unemployment rates as the expansion matured as well as during the pandemic.

FIGURE 13: Unemployment Rate by Gender, New York, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

In 2015, both the number of men and women in New York’s labor force were at their highest levels since the end of the Great Recession. Over the next two years, women continued to add to their labor force numbers (92,000), while, by 2017, there were 6,000 fewer men.

FIGURE 14: Cumulative Change in Labor Force by Gender, New York, 2016-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

From 2017 to 2019, men continued to leave the labor force but women also began to drop out, at a slightly higher rate than the men. However, in 2020, New York’s labor force had 123,000 fewer men, 2.5 percent, than in 2019, compared to 85,000, 1.9 percent, fewer women. Although a larger number of men reentered the workforce in 2021, it was 6,000 fewer than those who left in 2020. On the other hand, the women who returned exceeded their pre-pandemic level by 12,000.

With women more likely to be stay-at-home parents and caregivers, the labor force participation rate for women in New York is much lower, 54.1 percent compared to 65 percent for men in 2021. However, even though there are more women in the workforce in New York than the rest of the nation, their participation rate is lower in New York. In fact, a higher share of both genders nationally participates in the workforce. (See Figure 15.)

FIGURE 15: Labor Force Participation Rates by Gender, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

Participation rates for both men and women in New York have declined over the past 10 years, by two percentage points. For the rest of the nation, the participation rate for men declined at a higher rate, 2.9 percentage points, than in New York; for women, the decrease was the same.

As noted previously, during the pandemic, men dropped out of the labor force in larger numbers than women resulting in a higher decline in the participation rate, a decrease of 1.4 and 0.8 percentage points in 2020, respectively. Participation continued to fall for both genders in 2021, women at a slightly higher rate than men.

Race/Ethnicity

While the labor force in New York is predominantly white, it has gotten more diverse in the past decade and is more so than the rest of the nation. The share of white workers has declined from 75.8 percent in 2011 to 70.9 percent in 2021. As shown in Figure 16, New York has greater shares of Black or African American, Asian and Hispanic workers than the rest of the nation.

FIGURE 16: Share of Labor Force by Race/Ethnicity, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

Despite being a small portion of the total labor force, the number of Asian workers in New York realized the largest growth from 2011, 43.2 percent, increasing to over 10 percent of the workforce in 2021. (See Figure 17.) This was also the only racial demographic to add workers during the pandemic.

There has also been strong growth in the number of people of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity in the New York labor force: 22.4 percent over the 10-year period.7 As a result, 18.6 percent of the labor force was comprised of Hispanic or Latino workers in 2021.

FIGURE 17: Change in Labor Force by Race/Ethnicity, New York, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

For most of the last decade, Whites had higher labor force participation rates in New York, as shown in Figure 18. However, in the six years leading up to the pandemic, participation rates for this cohort stagnated, averaging 61.3 percent, one and one-half percentage points below 2013. While rates for all races decreased during the pandemic, that for Whites was the only one to continue to fall in 2021.

Labor force participation by Black or African Americans has been decreasing steadily from 2014, reaching a low of 55 percent in 2020. However, participation rebounded in 2021, almost half a percentage point higher than its pre-pandemic level.

In the past five years, those of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity had the highest participation rates. Unlike the different races, participation rates by this group did not fall during the pandemic and then grew in 2021.

FIGURE 18: Labor Force Participation Rates by Race/Ethnicity, New York, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Age

For both New York and the rest of the nation, the labor force is predominantly ages 25 to 64, the age range when the population is generally finished with their education and has yet to enter retirement. As shown in Figure 19, New York has a higher share of its labor force that is older, aged 65 and over. On the other hand, the rest of the nation has a larger share of workers aged 16 to 24.

FIGURE 19: Composition of Labor Force by Age, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

From 2011 to 2021, the working age population in New York increased by 3.5 percent, however, the labor force decreased by 1.0 percent. During this time, both the population and the labor force under the age of 65 declined, by 2.6 percent and 2.2 percent, respectively.

Figure 20 shows the change in the population and the labor force for various age groups. Within the age groups, the population aged 65 and older grew significantly over the decade, by 32.8 percent, to comprise 22.1 percent of the population in 2021, nearly five percentage points higher than in 2011. Similarly, the number of workers 65 and over increased by 42.6 percent, from 4.9 percent of the labor force in 2011 to 7.1 percent in 2021.

FIGURE 20: Change in Population and Labor Force by Age, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

A total of 209,000 workers fell out of the labor force in New York between 2019 and 2020. Of these, most were aged 25 to 44, but workers aged 65 and over dropped out at the fastest rate, a decline of 9.3 percent. However, not all age groups had smaller labor forces; there was an influx of 5,000 workers aged 16 to 24. Those aged 16 to 24 continued to add to the labor force numbers in 2021 and there were 59,000 more workers aged 45 to 64 in 2021 than in 2019. More than three-quarters of those between 25 and 44 and just over half those aged 65 and over returned, but these numbers were still below pre-pandemic levels.

Like the distribution of the labor force by age for both New York and the rest of the country, the participation rates for both the younger and older populations are much lower than that for those of prime working age.8 However, as shown in Figure 21, participation rates for most of the age cohorts are lower than those nationally.

The largest difference in the participation rates is for those aged 16 to 24, New York being almost six percentage points lower. A possible reason for this disparity may be New York has a higher percentage of its population aged 16 to 19 enrolled in school compared to that nationally. In addition, of the enrolled population, a smaller proportion is in the labor force in New York.9

Between 2020 and 2021, the participation rate for older workers fell by 1.8 percentage points, but the sharpest decrease was for the youngest age group, which declined by 3.4 percentage points.

FIGURE 21: Labor Force Participation Rates by Age, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

Educational Attainment

New York has a well-educated workforce. As shown in Figure 22, just over half of the State’s labor force aged 25 and over had a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2021 compared to 43.3 percent for the rest of the nation.10

FIGURE 22: Share of Labor Force by Educational Attainment, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

While workers with more education tend to be paid higher wages, workers at lower education levels include tradespersons such as mechanics, electricians, and plumbers. Those with less than a bachelor’s degree can also include construction workers, various types of technicians, as well as health care assistants and aides. Many of these occupations have wages higher than the statewide median but have seen their numbers decline in New York.11

In the past 10 years, both the working age population as well as the labor force in New York with a bachelor’s degree or higher increased significantly, by 34.6 percent and 26.3 percent, respectively. However, as Figure 23 shows, at all other educational levels, both the population and labor force declined.

FIGURE 23: Change in Labor Force by Educational Attainment, New York, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

During the pandemic, there was no loss of workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher; the labor force for this group grew by over 100,000 workers in 2020 alone. However, at the lower educational levels, workers dropped out of the labor force in 2020, with the largest number being high school graduates. A potential reason for this is a larger percentage of workers at the higher education levels were able to telework during the pandemic. According to BLS, the share of those nationwide with bachelor’s degrees or advanced degrees that worked from home due to COVID-19 were 40.6 percent and 54.4 percent, respectively. These shares dropped significantly for those with less than a four-year degree or just a high school diploma.12 As noted previously, workers at these educational levels tend to be tradespeople and those with public-facing jobs.

Workers with a high school diploma continued to drop out in 2021. While the labor force for all other educational levels increased post-pandemic, the number of workers with less than a high school diploma and those with some college remained below 2019 levels.

Labor force participation increases as educational attainment increases, as shown in Figure 24. In 2021, the participation rate in New York for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher was 71.9 percent, nearly 13 percentage points higher than the statewide average. However, those workers with less than a high school diploma are less likely to be in the labor force, with a participation rate of just under 41 percent.

FIGURE 24: Labor Force Participation Rates by Educational Attainment, New York and Rest of United States, 2021

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; OSC calculations

Compared to the rest of the nation, only the participation rate for workers with some college was higher in New York. While participation for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher was relatively the same between the two, the gap was much wider for those with a high school education or less.

Disability

People with disabilities comprised 8.8 percent of the population in New York aged 18 to 64 in 2020 (the latest data available), lower than the 10.3 percent share in the rest of the nation. In relation to the labor force, that share was also smaller, only 4.6 percent of the New York labor force compared to 5.7 percent for the rest of the country; this was up from the 4.4 percent and 5.5 percent shares, respectively, from five years prior.

Labor force participation for this group trails that for the State as a whole, as just 40 percent of people with disabilities participated in the New York labor force in 2020.13 While not much higher, the national participation rate was 43 percent. However, this was a slight improvement from five years ago when the State and national rates were 39 percent and 41 percent, respectively.

Unemployment rates among people with disabilities in New York are historically higher than for the non-disabled. As seen in Figure 25, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities was at its lowest in over 10 years in 2019, but grew in 2020 and remained elevated in 2021, at a rate almost twice that of people without a disability.

FIGURE 25: Unemployment Rate in New York, People With and Without Disabilities, 2011-2021

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics & Office of Disability Employment Policy

Unionization

Union members represented 10.3 percent of all employed workers nationwide in 2021, down from 11.8 percent in 2011. In New York, the 22.2 percent of employed workers that were members of unions was the second highest in the nation. Hawaii had the highest union membership, 22.4 percent, while South Carolina had the lowest, 1.7 percent.14

Like that nationally, the share of the employed labor force in New York that were members of unions declined over the past 10 years. However, New York’s decline was at a higher rate, falling by almost two percentage points, from 24.1 percent in 2011.

In New York, two-thirds (66.7 percent) of public sector employees were union members, compared to 13.1 percent of private sector workers.15 For both sectors, the level of membership is down from 10 years ago, with the biggest decline in the public sector membership, 5.5 percentage points lower. A potential reason could be those industries with the highest declines in union membership nationwide over this period are those with some of the highest shares of employment in New York. In addition, these industries had some of the largest declines in employment during the pandemic and have yet to recover those lost jobs.16

Nationwide, just over one-third (33.9 percent) of public sector employees were union members in 2021, down from 37 percent in 2011. Membership among private sector workers realized a small decline, from 6.9 percent in 2011 to 6.1 percent in 2021.

Conclusion

Employment is a good indicator of the health of an economy, but it is only half the picture. Jobs numbers represent people employed by a business at a given time and reflect the location of the employer and not the employee. Labor force statistics complete the picture as they are based on where the worker lives and not where they work, with their incomes enhancing the economies in which they live.

New York has a well-educated workforce with an increasing share achieving a four-year degree or higher, an encouraging characteristic in a skills-based economy. Well-educated workers were also able to better weather the pandemic as they were more able to telecommute. However, New York has lost workers at the lower educational levels. These include not only salespersons, waitstaff and grocery clerks, but also tradespersons such as electricians, plumbers and mechanics. Shortages of these workers can adversely impact the State’s economy.

More broadly, New York’s labor force was shrinking even before the pandemic. This was due not only to a declining population, but also a smaller share of the State’s population participating in the labor force. Even though the State’s workforce has been growing in 2022, it is still down by over 400,000 people from its peak in December 2019. Shrinkage of the workforce and populations in many regions of New York pose challenges to achieving overall economic growth in these areas and ensuring the long-term vitality of local communities. This trend could also result in fiscal and budgetary issues for the State and local governments. These and other issues associated with changes to the labor force merit continued attention and should be analyzed more closely as policymakers consider priorities and programs to best ensure that all regions of the State can grow and thrive.

While New York’s labor force is large, diverse and well-educated, attention should be paid to its underlying structure to attract and retain workers. To grow and maintain a healthy economy, New York must be able to create good jobs for all its residents.

Endnotes

1 Employment figures are reported by businesses and reflect persons on the payroll; they do not include jobs the business may have open/waiting to fill. These figures also reflect the location of the business and not the residence of the workers. For example, a business with operations in New York City may have workers who are residents of Connecticut or New Jersey. In addition, the jobs being counted are non-agricultural payroll jobs and encompass full-time, part-time, temporary and seasonal employment. One worker may be working two or more of those jobs.

2 Data for this report are drawn primarily from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, supplemented by the New York State Department of Labor, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, and the U.S. Census Bureau, 2016-2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Figures in the report represent annual averages unless otherwise indicated.

3 New York State Department of Labor, Comparison of U.S. and New York State Recessions, at https://dol.ny.gov/index-coincident-economic-indicators-icei.

4 The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program provided unemployment benefits to the self-employed, agricultural workers, and others, including those who quit their jobs, had an insufficient work history, or were diagnosed or had to care for a family member with COVID. The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) and Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) programs extended or provided additional benefits.

5 The underemployment rate is the sum of the officially unemployed, discouraged and other marginally attached workers, and workers employed part-time for economic reasons as a percentage of the sum of the total labor force plus discouraged and other marginally attached workers.

6 While the participation rate was slowly increasing in the months just prior to the pandemic, it had been consistently decreasing every year since the Great Recession. Among the eligible recipients under PUA were people who were supposed to start employment but could not due to COVID. This would include people such as high school and college students who may have had a summer job or post-graduate employment but were not able to work. As these people have typically low labor force participation, they would not necessarily contribute to lower rates as they were already not counted as part of the labor force. The same could be said of those with an insufficient work history, such as a parent who just returned to the workforce. If COVID disrupted this return, the person would not have previously been a labor force participant.

7 While the data on labor force provided by BLS are presented by race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, the statistics for workers based on racial identity are not exclusive of the Hispanic or Latino population. As a result, the figures related to the Hispanic or Latino ethnicity category are also incorporated within the race statistics, depending upon the race with which the person identifies.

8 While BLS typically refers to the prime working age as workers between the ages of 25 and 54, for purposes of this report, it is defined as such for those between 25 and 64.

9 U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 American Community Survey, 5-Year Estimates, at https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=population%20by%20school%20enrollment%20and%20age&g=0100000US_0400000US36&tid=ACSDT5Y2020.B14005.

10 BLS publishes data on educational attainment primarily for those aged 25 years and older as most people have completed their schooling by age 25.

11 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, at https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm.

12 Matthew Dey, Harley Frazis, David S. Piccone Jr, and Mark A. Loewenstein, "Teleworking and Lost Work During the Pandemic: New Evidence from the CPS," Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 2021, at https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2021.15.

13 Participation rate is for the disabled population aged 18 to 64.

14 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics (CPS), Union Affiliation of Employed Wage and Salary Workers by State, at https://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpslutab5.htm.

15 Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson, "Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey: Note," Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 56, No. 2, January 2003, pp. 349-54 (updated annually at https://unionstats.com/).

16 These industries include government, health care and social assistance, leisure and hospitality, and wholesale and retail trade.